Machismo in Costa Rica: How Tradition Meets Transformation

In Costa Rica, machismo is more than a word. It represents a set of social expectations around masculinity: strength, emotional restraint, authority, and the role of provider. Psychologists and social researchers define it as a learned socialization of gender norms, which can manifest in behaviors that privilege men while limiting women, and sometimes men themselves.

Long Before the Colonizers: The Indigenous Roots of Costa Rica

Understanding the history and contributions of Costa Rica's Indigenous peoples is essential for appreciating the nation's rich cultural tapestry. It's important to approach their cultures with respect and humility, recognizing their resilience and the invaluable knowledge they offer.

As Costa Ricans, we must honor the legacy of the pueblos indígenas (Indigenous peoples) and support their efforts to preserve and promote their cultures for future generations.

Shadows and Sunlight: The Story of Slavery in Costa Rica, the U.S., and the Caribbean

Costa Rica’s story comes alive through human narratives. Ana Cardoso’s life, the worship of La Negrita (the little black one), and the Afro-Caribbean traditions in Limón reveal that slavery was not only a legal institution but a deeply human experience. DNA studies show early mixing of European, African, and Indigenous populations, demonstrating that mestizaje (racial mixing) was foundational to Costa Rican society (Morera-Brenes & Meléndez-Obando, 2016).

The legacies of slavery persist: social marginalization, economic gaps, and cultural invisibility. Yet there is also richness—music, food, festivals, and community bonds testify to the resilience and creativity of Afro-descendant populations.

Pura Vida: More Than a T‑Shirt Slogan — The Pure Life of Costa Rica

“If someone asked me to describe my country in one or two words, I wouldn’t think twice,” writes Costa Rican educator Nuria Villalobos. “Pura Vida would be the answer. It symbolizes the idea of simply enjoying life and being happy.” (DiLonardo, 2015) costaricantimes.com+2costaricantimes.com+2

And indeed, the phrase appears everywhere: in greetings, we farewells, in gratitude, in admiration. “Pura Vida!” can mean “I’m good,” “Everything’s cool,” “Thanks,” “Let’s roll”—or even just “Wow, this is beautiful.”

Linguistic research shows that pura vida has become “a prime way of establishing claims to Costa Rican identity”—a kind of verbal badge that says: I am tico. I belong here. (Stewart, 2005)

Bananas, Blood, and the Caribbean Coast: The Costa Rican Story

Wages for banana workers in Costa Rica are higher than in many other Latin American countries, but still often fall below a true living wage. According to CORBANA (2024), the average gross salary for a banana worker is ₡ 364,769/month (~US$600–650), exceeding minimum wage but below the estimated living wage in Limón province (₡ 414,981/month).

Costa Rica’s Hammer of Peace

On December 1st, at the old barracks of Cuartel Bellavista — now the Museo Nacional — José Figueres Ferrer lifted a mallet and struck the wall of the old barracks. The blow didn’t end an army; it announced an intention. The real transformation came months later, when the Constituent Assembly wrote the abolition into the 1949 Constitution. According to UCR historians, this decision was not impulsive but strategic: a deliberate effort to prevent military influence over elections, coups, or governance. It was, as many Costa Ricans later described it, “una decisión valiente de un país pequeño, pero con un corazón enorme.”

How Do Ticos Do It?

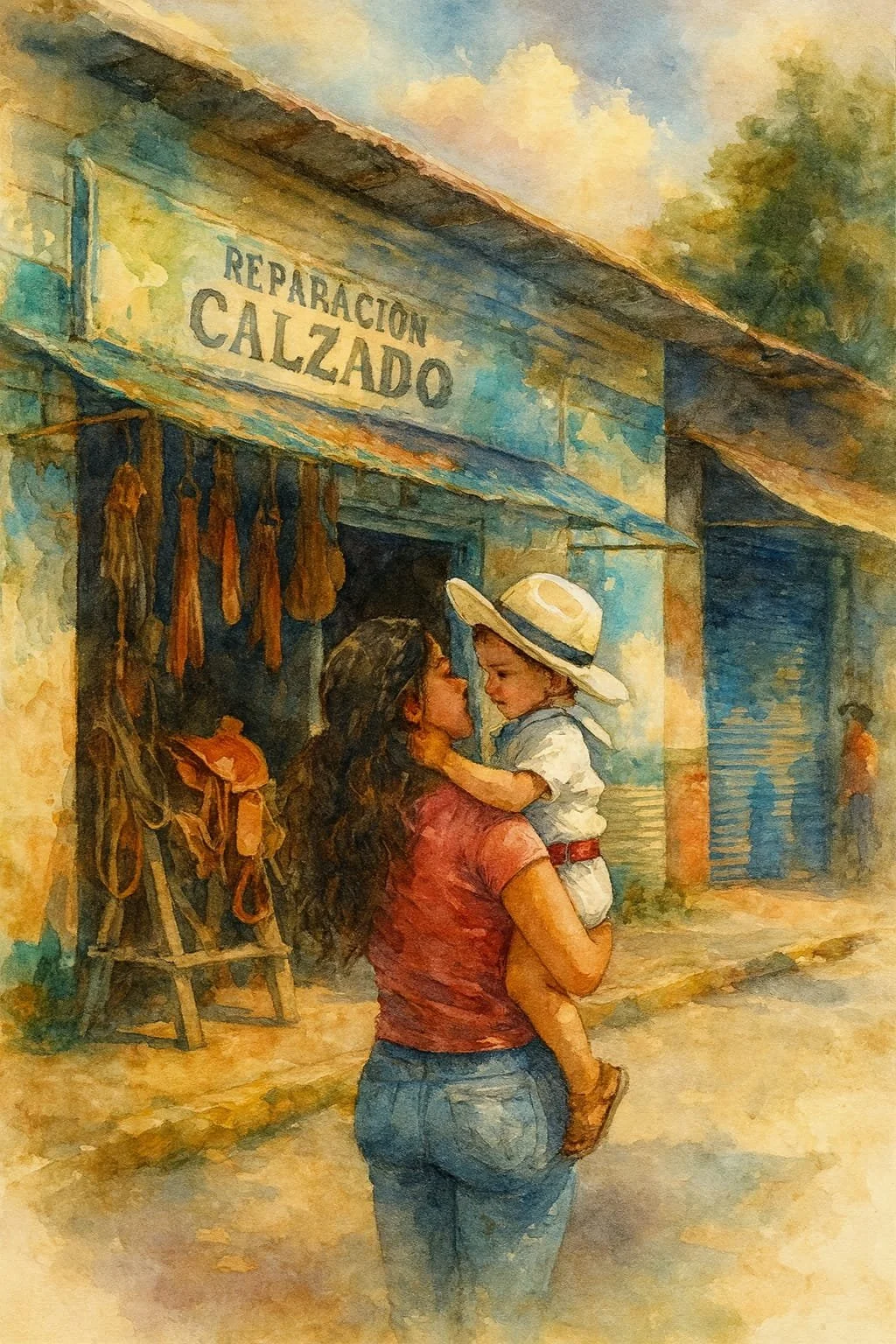

Costa Rica is often romanticized as “pura vida,” but for many ticos, la vida is neither glamorous nor easy. As beach towns gentrify and foreign money pours in, the traditional, simple Costa Rican life is under real pressure. The question “how do ticos do it?” sounds innocent, but the true answer is - with grit.

Life Inside the Blue Zone That Can’t Be Bought

Step into almost any home in Nicoya’s Blue Zone or its surroundings, and you’ll find black-and-white portraits on the walls — faces from another century. They’re not antiques. They’re family. And each one of them has something to teach you about time. The faces stare back at you from another century, framed in teca (teak), surrounded by the faint smell of café (coffee) and smoke from the fogón (woodstove). They are reminders of a time when everything — the pace, the noise, the ambitions — moved slower. When people lived long not because they were trying to, but because life itself demanded paciencia (patience).

You think that’s an exaggeration. Then you meet Don Vicente, who walks two miles uphill every morning before coffee, eats a chorreada (corn pancake) with natilla (sour cream) made his daughter, and tells you he remembers when cows were the only alarm clocks. He’s 94 going on 49. You think he’s an old man who’s lost his marbles as he sits with his guíjula (a long stick to drive oxen) looking out at the pampa (prairie) — and then you talk to him and realize he has way more marbles than most. His mind is sharper than a new machete, and his humor could light a galerón (rustic large shed). When he talks, you realize he’s not reminiscing — he’s teaching, in the same way his father once taught him, without ever calling it that.

Between Two Seas: Costa Rica’s Symbols of Identity

Costa Rica’s national symbols are far more than decorative flourishes. They collect geography, history, values and aspiration into compact emblems. Each illustrates how the country understands itself and wishes to be understood. Below are five of those symbols, their significance, and how the lives of Costa Rican figures help bring them into sharper relief.

Music in Costa Rica: A Story of Roots and Reinvention

One of the ironies is that while Costa Rica is a major tourist destination, the music that tourists often see is one slice of what’s happening. Beaches, resorts, hotels may play ‘Latin pop’ or generic tropical background music, but the deeper stories—folk fiestas in Guanacaste, calypso jams in Limón barrios, underground rap sets in San José—are more local and less curated.

If you listen closely, you’ll hear that many heritage forms are being preserved, even as they are reinvented. For instance, researchers in Limón have collected calypso songs, created cancioneros with lyrics and chords, to pass on the tradition.

The People Who Named the Rivers: A Hidden History of Costa Rica

Today, eight Indigenous peoples officially remain: the Bribri, Cabécar, Boruca (Brunka), Chorotega, Huetar, Maleku, Ngäbe (Ngöbe or Guaymí), and Brörán (Térraba). They occupy 24 legally recognized territories across the country — mountains, valleys, and plains that stretch from Talamanca to Guanacaste. Together, they represent roughly 2.4% of Costa Rica’s population, but they carry something immeasurable: the living continuity between pre-Columbian Costa Rica and the modern nation.

Reading Faces in Costa Rica: How Ticos Talk Without Words

Take the nose crinkle. In much of the world, it signals disgust. In Costa Rica? It says, “Wait, what did you just say?” or “Your turn.” It’s a polite, nonverbal nudge that the conversation is now yours.

Then there’s the lip point. Finger-pointing is considered rude in rural areas—too aggressive, too literal. Instead, Ticos will subtly purse or jut their lips toward a direction or object. It’s a quiet way of saying “over there” without offending anyone.

And those head movements? Don’t make the rookie mistake of assuming an upward nod is hello. Nope. In Costa Rica, that head tilt usually means “Que?”—“I didn’t catch that”. If you want to actually say hello, try a whistle or a casual verbal greeting instead.

Finally, the eyes. Ticos don’t look away shyly—they look with intent. Their gaze says, “I see you, I’m listening, I’m not going to bother you.” Mix in a slight smile, and you’ve got someone ready for a laugh, a story, or a little shared chaos with family or friends.

Costa Rica’s Carreta: From Workhorse to Cultural Treasure

If you’ve ever been lucky enough to be stuck behind a carreta (ox cart) in rural pueblo (small town) traffic, you’ve also sat in one of Costa Rica’s walking museos vivientes (living museums): some carretas are plain, weathered maderas(woods) of unfinished planks and rusted clavos (nails), and others are riotously painted emblems of familia (family) pride and identidad regional (regional identity). The story of how a utilitarian vehículo (vehicle) became a símbolo nacional(national symbol)—then a fragile tesoro cultural (cultural treasure)—is part historia artesanal (craft history), part historia social (social history), and part slow motion emergencia de conservación (conservation emergency). (UNESCO; Archivo Nacional).

Muñecones: The Giant Puppets of Costa Rica

The muñecones are more than just oversized puppets; they are symbols of Costa Rica's rich cultural heritage. They represent the fusion of Indigenous, Spanish, and Afro-descendant traditions, creating a multicultural tapestry that is uniquely Costa Rican. Through these giant puppets, stories of resistance, identity, and community are passed down, ensuring that the spirit of Costa Rica endures for generations to come.

Costa Rica’s Haunted Pen: Leyendas, Witches, and the Living Supernatural

Costa Rica is not just a tropical paradise—it’s a place where the sobrenatural (supernatural) brushes against daily life. From las montañas (the mountains) of Escazú to the deep forests of Guanacaste, leyendas (legends) of brujas (witches), fantasmas (ghosts), and mischievous duendes (spirits/trickster elves) are more than stories—they are expresiones(expressions) of a folclore (folklore) that remains vivid and alive. In pueblos (towns) and rural regions, belief in duendes, espíritus (spirits), and brujas (witches) continues, whispered in shadows and fog.

September 15

On September 15, 1821, five Central American nations—Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua—proclaimed their independence from Spain. It was not just a political act but a collective pivot, a moment when neighbors chose freedom together. The date became a shared anniversary, a symbolic shorthand for sovereignty and identity across the isthmus.

Look more broadly, and September itself begins to look like a season of revolution. Mexico declared on September 16, 1810. Chile followed on September 18, 1810. A century later, Belize entered independence on September 21, 1981, in the very same week. Other nations joined in the broader Latin American wave: Argentina, July 9, 1816; Colombia, July 20, 1810; Venezuela, July 5, 1811.

The clustering isn’t coincidence. Revolutions create momentum; ideas move faster than armies. What began with Bolívar’s campaigns in the north and San Martín’s in the south rippled outward until independence was less a question of if than when. By September 1821, the answer had arrived.

You Can't Separate Language from Culture: Learning Costa Rican Spanish

You can't separate a lengua (language) from a cultura (culture), and you can't separate a cultura (culture) from its dialecto (dialect). Just try. It's not going to work in a mejenga (pickup soccer game), in the plaza (central soccer field), in the barrio (neighborhood), between guilas (kids). The words matter. The inflections matter. The way someone says usted(you, formal) instead of vos (you, familiar) or slips in a tuanis (cool) matters because language is the map to understanding the people who inhabit it.

Fútbol in Costa Rica: More Than a Game, a National Heartbeat

Step into a Costa Rican neighborhood on a Saturday afternoon, and you’ll hear it before you see it: the thud of a ball against concrete, the cheers of niños darting across a dusty field, the whistle of a makeshift referee calling a corner kick. In a country of just over five million people, fútbol—soccer—is not merely a pastime; it is a heartbeat, a collective memory, and a dreamscape for boys and girls alike.

Every majenga—the informal street or beach game—reveals a microcosm of Costa Rican society: improvisation, negotiation, hierarchy, teamwork, and instinctive strategy. It’s not “just soccer”; it’s where resilience, creativity, and community are learned.

Saying Something Indirectly: The Art of Costa Rican Softness

What you don’t say matters just as much as what you do say. In Costa Rica, being too direct can feel frío, pesado, or even grosero. So, Costa Rican Spanish softens everything. Sociolinguists call it discreción afectuosa—affectionate discretion—a way of speaking where you create space for others. Ticos speak with kindness and familiarity. It’s a style of speech that respects your boundaries while inviting collaboration.

Stop Getting Stuck in the Present: Why the Past Tense is Easier Than You Think

Most Spanish learners do the same thing. They obsess over the present tense. “I eat, you eat, he eats…” over and over. And then they freeze the moment they try to talk about yesterday. But here’s the truth: the past tense—especially the pretérito—is far simpler than most people think. Linguists from top universities, from the Real Academia Española to Costa Rican language studies, agree: past tense is where Spanish really starts to make sense.